Rent Controls in Oregon Won’t Lead to More Affordable Housing

February 28, 2019| James Sprow | Blue Vault

Economics is one social science that provides millions upon millions of data points daily to test its theories. Most introductory courses in economics consider the effects of price controls generally and rent controls specifically to test whether those types of legislative initiatives produce the results that their proponents hope to achieve. There are many real-world examples to observe that suggest that rent controls do not succeed in providing more affordable housing and the theory behind that conclusion is not difficult to grasp.

When rents are determined by the forces of supply and demand in competitive markets, landlords compete to provide housing at various rental rates, balancing the variables of monthly rent, occupancy rates, maintenance and other operating expenses, and the long-term return on investment they are seeking when they purchase or construct rental properties. Quite simply, when rental rates are capped via legislation, landlords will adjust their behavior. Over the long run, they will change the way they maintain their properties, become more selective in the tenants they choose to lease to, reduce their investments in new apartments and in the upgrading of existing apartments, and, as has been observed in New York and elsewhere, consider converting rental units into condominium units.

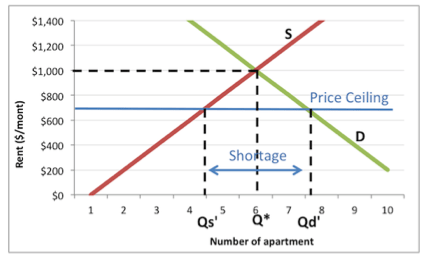

The future results of Oregon’s recent adoption of rental caps are sadly predictable. Any student in an introductory economics course should be able to explain on an exam a chart that illustrates the law’s likely effects. The unconstrained equilibrium rent in this example ($1,000) and the unconstrained supply of units (Q*) illustrates a market in balance. With rent controls, the quantity demanded (Qd’) is far in excess of the number of rental units supplied (Qs’) and a shortage develops. Both tenants and landlords are made worse off. Tenants who don’t need to move and who have their rents capped may benefit, but new tenants will find it more difficult to find housing at “affordable” rental rates. And landlords and investors in apartments will be less able to justify their investments as their returns are capped, reducing the supply over the long run.

Instead of making more “affordable” housing available, the most likely outcomes over the next few years in Oregon are a reduction in the supply of apartments below what would otherwise be provided, reduced maintenance expenditures, more selective landlords, and, unfortunately, more black-market transactions that skirt the law. Wherever government tries to legislate prices in otherwise competitive markets, the results are predictably unsuccessful, inefficient and contrary to their stated objectives.